Last year we wrote about the issues facing many syndicated multifamily assets that were acquired in the 2020 to 2022 timeframe. Unfortunately, those issues will continue to come to a head in 2024 for those assets that were acquired with variable rate, short-term “bridge debt.” The tone of this article is meant to be objective, but the subject will inherently lean negatively with respect to assets acquired in the hothouse environment of 2020 to 2022. The article is not meant to be insensitive to those investors who have capital at risk, as we often invest our own personal funds and can relate to all parties. But we also caution against extrapolating a negative perspective on multifamily in general or even a negative view on ALL multifamily assets acquired between 2020 and 2022. There are significant assets within this acquisition time frame that will perform for investors over a 5 or 7 year life cycle. Our firm has such assets in our portfolio. However, there are assets (including some in our portfolio) facing challenges and our goal in this article is to provide context for those challenges for investors. We’ll discuss some of the potential outcomes of those challenges in the second half of this article.

Context

Before we get ahead of ourselves, it’s first helpful to understand how “bridge debt” works and why it was used so prevalently in the acquisition of large multifamily assets between 2020 and 2022. While “agency debt” from Fannie and Freddie features fixed interest rates with longer terms (7 to 10 years), most bridge loans have variable interest rates with shorter repayment terms (usually 3 to 5 years).

It begs the question, why use bridge loans if agency loans could give operators a longer runway and rate protection to execute business models and perform for investors? A few reasons. First, the actions of the Fed in response to COVID allowed bridge loan interest rates to become very attractive to operators. However, the major reason operators turned to bridge debt was leverage. Many bridge loans allowed for higher loan-to-cost (“LTC”) proceeds than agency loans. Bridge lenders were more comfortable loaning higher amounts to operators than Freddie and Fannie.

Why was leverage so important? Two reasons. First, in the immediate post-COVID financial markets, there was an overflow of inbound liquidity that was driving up the prices of multifamily assets. Put more simply, a lot of new money was entering the asset class which made it a seller’s market. Getting higher leverage bridge loans allowed operators to make higher offers on properties and remain competitive with the surging number of buyers in the marketplace. Secondly, getting higher leverage from the lender allowed operators to raise less relative capital from investors. For example, on a $30 million acquisition, a 65% LTC agency loan meant 35% or $10.5m of the purchase price would need to come from investors. But, an 80% LTC bridge loan meant only 20% or $6m was needed from investors. This is important because less investor money meant less dilution of returns for those investors. This allowed operators to offer more attractive projected returns to investors.

One final word before moving on. These previous two paragraphs are overly simplified. There were many factors that went into selecting the best debt structure. And, the individuals who secured these loans were required (by the lenders) to have extensive experience, personal net worth, personal cash flow, and verified business models to qualify. Some of these operators were smaller firms with 20-30 deals of experience. Some of these operators were large firms with billions of dollars of assets under management.

Another relevant postscript to this is the subject of “rate cap” policies. An interest rate cap policy is essentially a type of insurance an operator would purchase to protect the asset against rising interest rates. Sometimes operators would purchase them of their own accord. Other times, operators would be forced by the lender to purchase a rate cap. These policies had 2 important components: strike price and term. Policies could be purchased for terms anywhere from 6 months to several years. Operators could buy rate caps that had a strike price that would give them up to 100% protection against higher rates or some proportion lower than that. The longer the term and the more interest rate protection the policy gave, the more expensive it was to buy it. (For a complete explanation on interest rate caps, click here to read an article by the company that creates, sells, and buys such policies)

Were operators and investors ignoring the likelihood of interest rate increases?

Not exactly. First, most operators were underwriting some level of interest rate increases into their underwriting models. However, those operators with 2020-2022 acquisitions were subject to a confluence of surprising risks—resulting in a compounding negative impact.

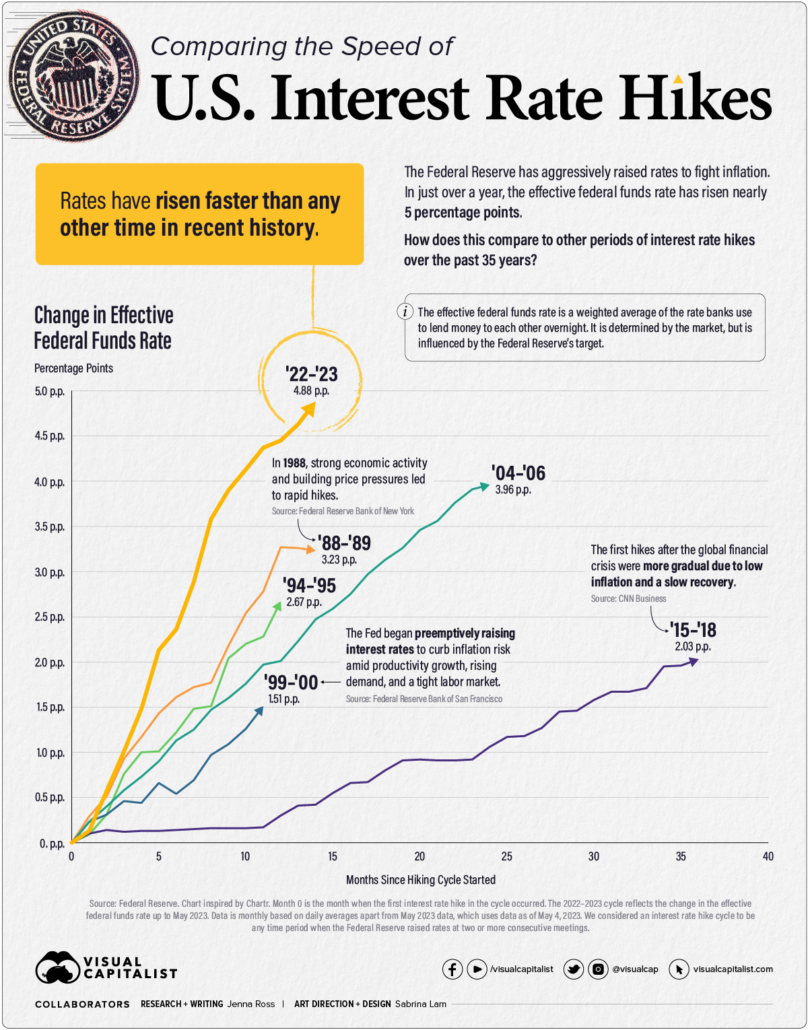

First, the Fed’s most recent tightening cycle was an anomaly compared to every other increase cycle of the last 35 years. This diagram below (source) gives a dramatic illustration of this point.

The nearly straight-up yellow line to the far left is the 2022-23 cycle. Compare that to the other tightening cycles in the illustration. It’s not necessarily that most operators didn’t expect interest rate increases—or else they wouldn’t have purchased interest rate caps and/or modeled rate increases into their sale and/or refinance projections. Rather, buyers didn’t project or expect the speed and magnitude of the fed rate increases given all other historical examples.

What’s been the impact of this rate cycle on operational finances for multifamily operators?

If the operator did not purchase an interest rate cap policy, the asset is on the hook for the entirety of that increased interest cost. It’s possible that a 5% interest bridge loan at the time of acquisition in 2021 is now carrying a 10 or 12% interest rate currently. If the operator purchased an “in-the-money” rate cap at closing, then they are receiving reimbursements from the policy that gives them an effective 100% protection against the higher interest rates. If the operator purchased a rate cap that protected against rates above 7%, for example, then the operator is absorbing the interest rate costs below 7% but getting reimbursed by the rate cap policy for anything over 7%.

In situations where there is either no-interest rate cap or interest rate caps with higher strike prices, the impact on the asset’s cash flow is tremendous. The effect may eliminate positive cash flow or even put the asset in a negative cash flow posture. When interest reserves and other cash reserves are depleted to cover these losses, the result is insolvency.

The other challenge is that most rate caps, if purchased, were structured with terms of 2-3 years. So, even those assets that have a 5 year bridge loan are facing a situation where the rate cap is expiring well ahead of that point.

That brings us to the current situation in which these assets now are in need of refinancing (or purchasing new rate caps). One challenge with refinancing in this environment is the much higher cost of debt. The interest rates to refinance are higher than what was projected. But, there’s a much bigger challenge for these 2020-2022 acquisitions: valuations.

Valuations

To understand valuations, we need a quick detour through multifamily underwriting. Operators understood that higher leverage bridge loans would need to be refinanced at some point into lower leverage agency debt (as refinancing a bridge loan with another bridge loan is pretty rare). To make that a cash neutral (or even cash out) refinance outcome, there would need to be an increase in valuation of the underlying asset. Conservative operators, contrary to critics, were not assuming valuations would passively rise with time. Actually, underwriting usually assumes some level of cap rate expansion or valuation decline. However, value-add business models deploy a “forced appreciation” strategy to achieve returns. This business model forces appreciation in the value of the asset by improving NOI (net operating income). As a rule, higher NOI equals higher asset value.

Many operators have been successful increasing NOI through forced appreciation strategies (remodeling units, increasing rents, reducing costs). Some operators, unfortunately, have faced challenges with unexpected operational cost increases, sourcing remodeling contracts, issues with 3rd party property managers, surprise changes to eviction processes, and contentious lenders changing or forbidding access to renovation capital reserves held by the lender.

Unfortunately, a market force with a much greater impact on valuations than NOI emerged half way through 2022 as the Fed tightened: liquidity.

Liquidity

The tidal wave of liquidity that entered the multifamily market in 2020 and 2021 created a valuation bubble. The blame may lie with lower interest rates, higher leverage, government stimulus and policy, etc. But, as interest rates increased so dramatically in 2022 and 2023, liquidity left the market. Lenders balance sheets were swollen with multifamily loans on the books. Leverage was greatly reduced which meant more investor capital was needed for acquisitions. At the same time, however, less investor capital was entering the multifamily asset class as stocks suffered and bonds and money markets started paying better returns to investors to park their capital on the sidelines.

With less buyers and less liquidity to purchase multifamily assets, basic supply and demand principles flipped the script. The same asset being sold in 2021 that had 20 bids from buyers had only 4 bidders in early 2023. In fact, through the first 3 quarters of 2023, there was only $89 billion in multifamily transactions compared to $250 billion in transactions in the first 3 quarters of 2022. While less buyers in the market means better buying opportunities, it also means valuations are lower in 2023/24 than they were in 2020 to 2022.

An important caveat to insert at this point is, once again, this is a very general, overly simplified breakdown of a very complex situation. We’ve not discussed Class A vs Class C multifamily assets. We’ve not reviewed the impact of geographic markets and submarkets on valuations (which is actually quite important). Likewise, we’ve omitted the impact of operator quality, cost basis, and a whole list of meaningful factors.

Even so, the reality is a large number of assets (and potentially billions of dollars of property) are facing a situation where they must now (or soon) refinance a property that is worth less than when it was purchased 2 to 3 years ago–and refinance it with less leverage to make matters worse. According to the Mortgage Bankers Association, “multifamily mortgage maturities (bank and nonbank) will surge from $184.9 billion in 2023 to $254.6 billion in 2024, accounting for 12.9% of multifamily loans outstanding. The MBA expects maturities to remain elevated during 2025 as well when the group predicts they will fall slightly to $242.6 billion or 12.3% of loans outstanding.” Essentially, one quarter of all multifamily loans will need to be settled in 2023-2024.

That was a long winded way of getting to the topic of potential outcomes for the current predicament for these assets.

What will happen to performing and nonperforming assets purchased in 2020 to early 2022 that now need to restructure debt and/or solve issues of insolvency?

Here’s 8 overly simplified potential outcomes.

Outcome #1: Purchase new rate cap and work to Outcome #2, 3 or 4 later on

If an asset has meaningful time left on its bridge debt, a simple option may be to buy a new rate cap policy. That can allow operators to continue their business model and position the asset for a refinance or sale down the road. The challenge for many assets is finding the capital to purchase new interest rate cap policies. Solutions may be finding capital from outside sources or from investors.

Outcome #2: Cash-out Refinance

This option is the best outcome for assets purchased in 2020-2022 with variable rate bridge loans. For those operators who purchased properties at a very attractive entry price and/or have successfully increased NOI, valuations may be such that the asset could be refinanced with agency debt and some portion of capital returned to investors in the process. The new debt structure puts the asset in a posture to succeed for investors long term.

Outcome #3: Cash-neutral Refinance

It’s also possible the healthy asset in outcome #2 may refinance into a fixed interest rate agency loan that neither gives cash back nor requires cash in. As with outcome #2, the new debt structure puts the asset in a posture to succeed for investors long term.

Outcome #4: Cash-in Refinance

A significant number of assets headed to a refinance will find valuations less today than they were 2 years ago at acquisition. When that is the case, the only way to refinance is to bring cash to the refinance to pay down some of the original debt. This is called a cash-in refinance. Most likely, the asset will not have enough liquidity to cover the capital needs of this process. So, where does the money come from? Here’s a few potential options:

4a: Member Loans from GPs and/or LPs

Some apartment syndications are preferring to look to their own members to find capital for cash-in refinances of their assets. Member loans, unlike capital calls, are usually voluntary. In essence, GP (general partners aka deal sponsors) and LP (limited partners aka investors) loan funds to the syndication in exchange for some amount of interest to be paid to the member. So as to not endanger cash flow, the interest and principal payments are often deferred until another capital event (sale of the asset).

4b: Capital Call

Most apartment syndications are structured to allow the operator to enact a capital call to investors. In this process, a request for a certain percentage of capital is requested from all investors. This does not function as a loan with interest owed to the investor. Rather, it’s essentially buying more equity in the asset. If members refuse the capital call, their equity position is diluted.

4c: Secondary loan from outside sources

If an operator cannot or will not look within the assets’ membership for capital, another option is to look for secondary loans from outside sources. In the current environment, these would be very high interest loans and would need approval by the lender that is refinancing the original debt. The cost of this secondary debt may be prohibitive in certain situations.

4d: Equity Partner

See next outcome

Outcome #5: Recapitalization

If an asset cannot refinance given the options in outcome #3 or if the asset is just simply not in a position to refinance, then recapitalization may be a potential outcome. Recapitalization is a very broad term referring to the influx of capital into an asset for a specific purpose. Perhaps, recapitalization is for the purpose of a cash-in refinance of the existing debt. Or the asset is in distress with no prospects of refinance and additional capital is needed to stabilize the asset for a refinance or sale down the road.

For the purpose of this discussion, we are defining recapitalization (or “recap”) as funds injected by an outside party into an asset for the purpose of obtaining outcomes otherwise not possible given the current capital structure.

It’s important to consider that recaps come in many different variations with many different outcomes for investors in the underlying asset. Some recap firms may agree to be preferred equity in the entity. This would entail the new partner sitting behind the lender and in front of the investors in the capital stack. After loan payments are made, a certain return on investment would be paid to the recap firm. In this scenario, investors would not be terribly diluted given the recap equity is most likely equivalent to the reduction in debt on the loan being refinanced. However, the returns to the preferred equity partner in this setup would reduce potential returns to investors in cash flowing assets post refinance. This flavor of recap is more likely when the underlying asset is performing well and will cash flow well after refinancing.

Another variation of the recap outcome is when the recap firm supplants the current operator on the asset, restructures the asset under a new entity, and modifies the equity and capital stack. In this scenario, the outcomes to existing investors in the apartment syndication are more detrimental, as their position will most likely be diluted and pushed further down the capital stack for repayment when the asset is finally sold by the new operator/firm. This variation of recap is more likely when no other recap opportunities exist and/or when the asset is experiencing some level of distress and/or the lender requires such a transition.

Outcome #6: Restructure current debt with lenders

This potential outcome is a hesitantly inserted item on our list, as it’s become increasingly apparent that lenders are not willing to restructure debt on these assets–as of yet. However, there are unique situations in which lenders may defer interest or modify other terms which allow operators to execute for a brief period to position assets for other long term solutions.

Outcome #7: Asset sale with partial to full loss to investors

When refinance options and capital solutions do not materialize, some 2020-2022 acquired multifamily assets will need to be sold if they do not have the cash flow or loan term runway to complete their business models. If valuations have fallen since acquisition, which is likely for 2020-2022 acquisitions, assets will be sold for less than they were acquired. Given that the lender is at the top of the capital stack, the loan would be paid back with sale proceeds first. Any proceeds left over after paying back debt would be distributed back to investors. This will result in losses for investors. The exact amount of investment loss would be contingent upon how much proceeds are left over after repaying debt.

Outcome #8: Foreclosure with full loss to investors

Finally, there may exist situations in which an asset has no capital solutions and the valuation is less than the amount owed on the asset and a sale is not feasible. With no other options available, the lender could foreclose on the asset. In such a situation, there would be a complete loss realized by investors. Operators and key principals who signed for the loan may have great difficulty acquiring loans for other assets in the future.

Conclusion

Is the multifamily asset class doomed to fail?

As an asset class in general, no. Apartment syndications performed well prior to 2021, many have continued to perform well during 2021-2023, and many will do so in the future. The above discussion was regarding a portion of the asset class that was acquired in 2020 to 2022 with variable rate bridge debt with ongoing exposure to lending terms and operational challenges. There are many properties and syndications that are still performing well.

In addition, there’s been a return to normalcy with respect to both valuations and debt structure in multifamily. While transactions were greatly reduced in 2023, fixed-rate agency loans were again a primary means of leverage for acquisitions of assets. Fannie and Freddie loan volumes have increased dramatically as more buyers turn away from higher leverage, variable rate bridge loans. Our firm was involved in only 2 acquisitions in 2023; both were A-quality assets in A-quality submarkets and acquired with fixed-rate agency debt—which was a directional shift in our firm’s focus compared to 2021 and 2022.

And, with the Fed most likely done raising rates, there’s increasing confidence that the bottom has formed in valuations for many properties in this asset class. This means those who are taking advantage of 2023 and 2024 buying opportunities will be able to better realize the benefits of buy-low-sell-high over the next few years.

And, with all real estate….location, location, location. Markets—more specifically, submarkets—are providing considerable segmentation within multifamily valuations. Midwest continues to be a bright spot for many multifamily operators. This will be especially true of buyers taking advantage of the current market in 2023 and 2024 that is providing buy-low opportunities.

Still, multifamily headaches will remain in the spotlight for all the reasons discussed in this article. The transition from valuation cycles will need to come to a completion as operators, lenders, and investors handle the fallout of 2021-2022 multifamily acquisitions.